EMDR & Trauma-Informed Care: Reflections from My First Year in an MSW Program

I’m wrapping up my first year in an MSW program, and one of the biggest shifts in how I think about practice came from learning about EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) through a trauma-informed lens. I don’t practice independently (yet!), but I’ve gathered research, read case material, and debriefed with supervisors who use EMDR. What follows is how I make sense of EMDR, why it fits so well with trauma-informed care (TIC), and what I’ll carry into year two and beyond.

What EMDR Is—in Student Speak

EMDR is a structured therapy that helps people reprocess distressing memories so they feel less vivid, less “now,” and more truly in the past. The therapist guides brief attention to a memory while using bilateral stimulation (eye movements, taps, or alternating sounds). Between short sets, the client checks in, and the therapist keeps things paced and grounded.

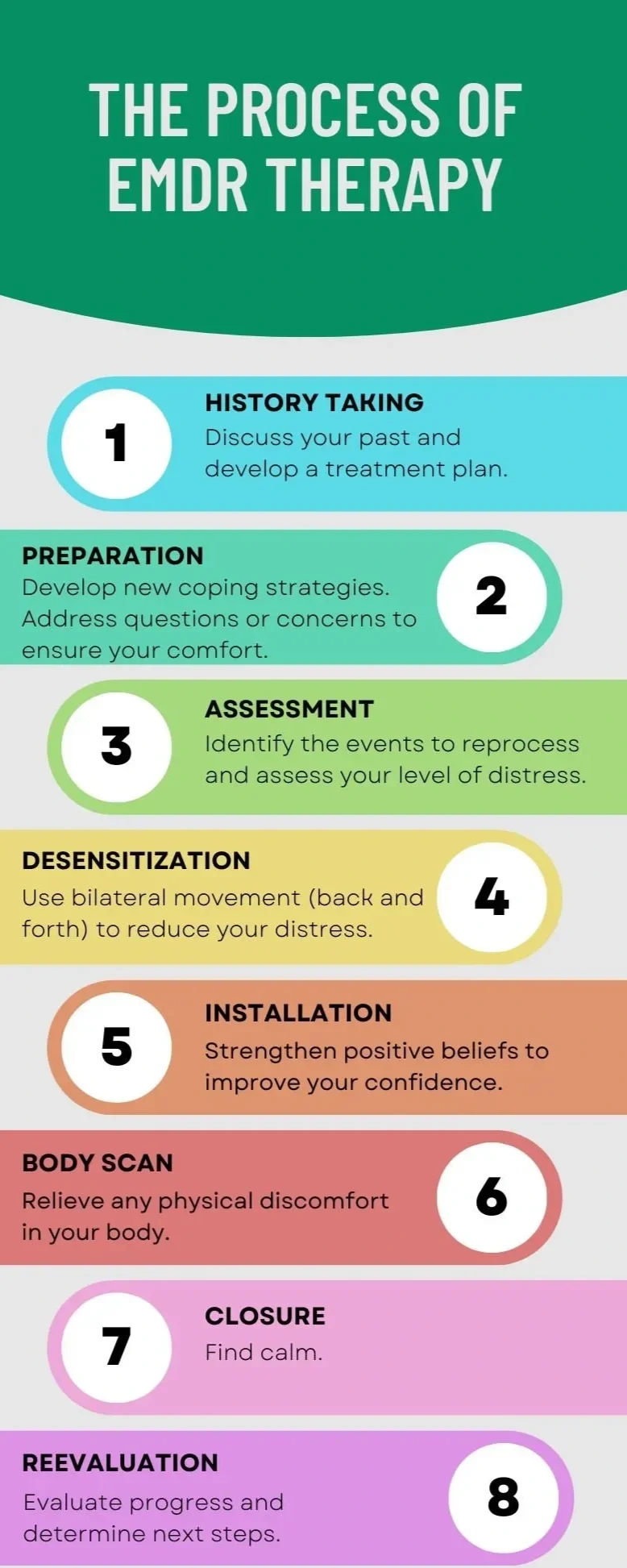

Most EMDR follows eight phases (history → preparation → assessment → reprocessing → installing positive beliefs → body scan → closure → reevaluation). What stood out to me is that Phase 2 (preparation) is not a speed bump; it’s the road. Before any memory work, clients learn regulation skills, set a stop signal, and choose the pace. That alone screams “trauma-informed.”

Underneath EMDR is the Adaptive Information Processing model: when experiences are overwhelming, the brain may store them in “raw,” isolated ways. Reprocessing links those memories to healthier networks, so current triggers don’t keep setting off old alarms.

Why EMDR Fits Trauma-Informed Care

Early in the program we learned the core TIC principles: safety, trust, choice, collaboration, empowerment, and cultural/historical responsiveness. Here’s how I see EMDR lining up:

Safety. Preparation builds real skills like grounding, breathing, and containment. Sessions aim for titration, not flooding, and the client can stop the process at any time.

Trust & Transparency. The eight-phase map is explained up front; clients know what’s happening and why.

Choice & Collaboration. Clients help choose targets and the form of bilateral stimulation. EMDR uses dual attention, one foot in the memory, one in the present, so the client stays in the driver’s seat.

Empowerment & Voice. EMDR doesn’t force a blow-by-blow retelling. The therapist follows the client’s brain as it connects dots, and the client decides what beliefs fit now.

Cultural/Contextual Care. Targets aren’t only single events. They can include racism, displacement, medical trauma, community violence, and other system-level harms.

From my practicum, the most trauma-informed sessions felt less like “telling the worst thing that happened” and more like building enough safety so the body could finally loosen its grip on it.

What It Looks Like in Real Life (De-Identified Scenarios)

Single-incident trauma:

A client with panic while driving after a crash. We spent several sessions on breathing and containment imagery before touching the memory. During reprocessing, the client’s belief shifted from “I’m not safe on the road” to “I can handle this moment.” Their shoulders literally dropped by the end.

Complex trauma:

A client with a history of family violence and chronic hypervigilance. Targets weren’t just “big T” events; we worked with body sensations and feelings that show up in everyday conflict. The pace was slower, with lots of resourcing between short sets.

In both cases, consent and pacing were the point, not a formality.

When EMDR Helps—and When to Stabilize First

Often helpful for: single-incident traumas, complex/childhood trauma, traumatic grief, moral injury, some phobias and anxiety presentations.

Stabilize first if: there’s active suicidality, uncontrolled substance use, psychosis, severe dissociation without grounding skills, or unsafe living conditions.

What I’m Taking Into Year Two

For Clients (and myself)

You get to set the pace. If the body says “too much,” that’s data, not failure.

Regulation is treatment, not homework. Skills like paced breathing, bilateral tapping, and grounding aren’t warm-ups; they’re the medicine that makes reprocessing possible.

Voice is bigger than words. Art, ritual, writing, and community remembrance can be part of healing—especially when language isn’t the safest route.

For Practice (as a learner)

Overprepare rather than underprepare. I’d rather spend extra sessions resourcing than risk reenactment.

Name power and context. Connecting symptoms to systems reduces shame and supports advocacy.

Offer choice points constantly. Targets, pace, stimulation mode, and whether we keep going today; choice is the intervention.

Co-regulate. My nervous system matters. Slowing my cadence, grounding myself with the client, and tolerating silence can make the room a safer space.

Common Misconceptions I Had (and What I Learned)

“It’s just eye movements.”

The eye movements (or taps) are one tool. The change comes from a structured process within a safe relationship.

“EMDR makes you relive everything.”

Done well, it reduces overwhelm through short sets and dual attention.

“It works the same for everyone.”

TIC reminds us to individualize—goals, targets, culture, history, and nervous-system patterns shape the work.

Questions I Now Ask Supervisors (and EMDR Therapists)

How do you decide someone is ready for reprocessing?

What’s your plan if activation spikes mid-set? (Stop signal? Resourcing?)

How do you integrate case management or advocacy when trauma is ongoing?

These questions help me keep the focus on safety, consent, and context, not just protocol.

Final Thought

My biggest takeaway as a first-year MSW student: EMDR and trauma-informed care share the same heart. EMDR offers a precise way to unlock stuck neural networks; TIC makes sure we follow a treatment plan with the client, at their pace, and with deep respect for culture, history, and choice. When those pieces come together, “what happened to me” shifts from a constant alarm to a past-tense story and one that the client can hold with more calm, meaning, and control.

Student note: This post reflects my learning and practicum observations, not clinical advice. If you’re considering EMDR, talk with a licensed clinician trained in EMDR to see if it’s a fit for your needs.