Why Polyamory Hinges on Informed Consent

Why Consent Forms the Foundation of Ethical Polyamory

Consent in polyamory is the ongoing, informed agreement among all partners to participate in a non-monogamous relationship. It’s not a one-time conversation but a continuous process requiring honest communication, clear boundaries, and the freedom to say yes or no at any point.

Key principles of consent in polyamorous relationships:

- Freely given - No pressure, coercion, or manipulation

- Informed - All partners have complete, honest information

- Enthusiastic - Active desire to participate, not just the absence of "no"

- Specific - Consent to one thing doesn't imply consent to everything

- Revocable - Anyone can change their mind at any time

- Ongoing - Regular check-ins and communication are essential

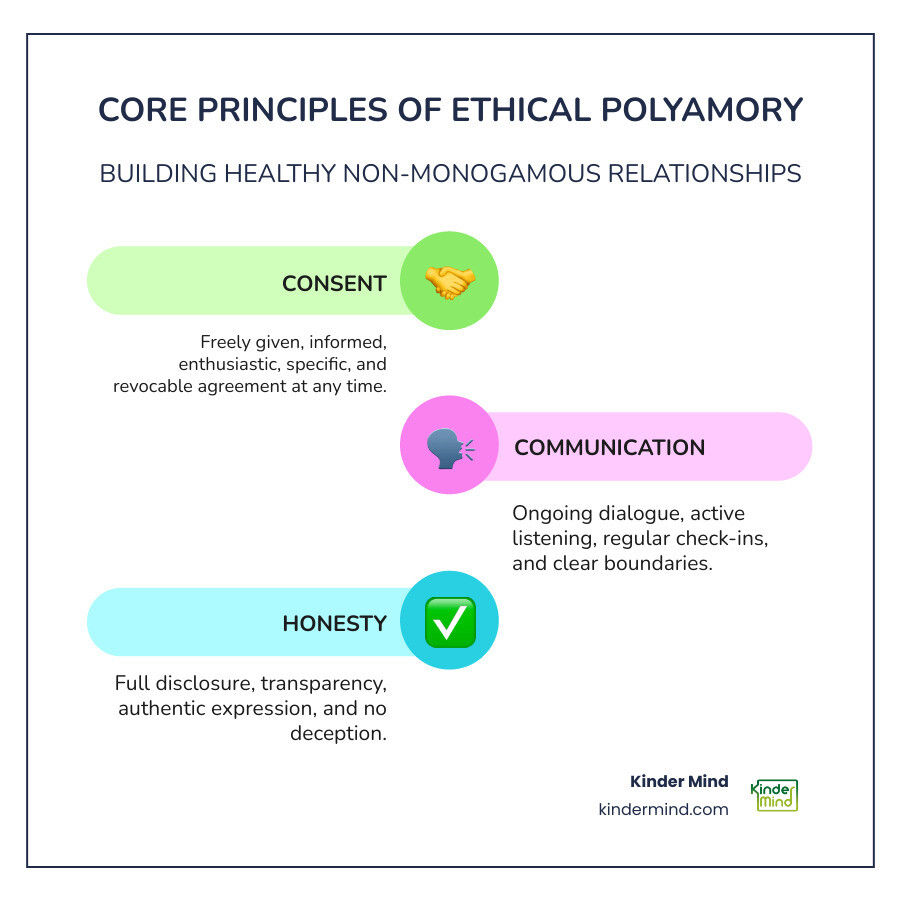

Many Americans have tried or want to try consensual non-monogamous relationships, but the word "consensual" is critical. Without genuine, informed consent from everyone, non-monogamy isn't ethical—it's cheating. The foundation of ethical polyamory rests on consent, communication, and honesty. These are the minimum requirements for treating partners with respect.

Real consent isn't about convincing a reluctant partner or ticking a box. It means proceeding only when it’s what everyone truly wants and being willing to stop the moment that changes. This is vital because pressure and manipulation can masquerade as consent. A partner who agrees to polyamory to save a relationship hasn't truly consented; they've been coerced.

Understanding consent in polyamory is about creating relationships where everyone feels valued, heard, and empowered to voice their needs and boundaries.

What is Consent in Polyamory and What Makes It Valid?

Consent in polyamory is more than just saying yes; it's an ongoing, expressed willingness to participate in a relationship dynamic. It's the thread that weaves through every decision and new connection.

When people start exploring ethical non-monogamy and polyamory, they learn consent is a living process that respects each person's autonomy—their right to make choices about their own life and body.

How is informed consent different from simple agreement?

A simple agreement ("Yeah, okay") is often passive and based on assumptions. You might agree without grasping the full implications.

Informed consent is different. It means you have all the relevant information before saying yes, including potential risks and emotional impacts. It’s about understanding what you’re actually agreeing to, not just going along to keep the peace.

For example, if a partner suggests "dating other people," informed consent requires conversations about safer sex, how much detail to share, how new connections might change your dynamic, and what emotional support everyone might need. Without these talks, you're flying blind, and mismatched expectations can lead to hurt.

What are the key components of valid consent?

Valid consent has five essential elements, often remembered by the acronym FRIES. These are the requirements for consent to be meaningful.

- Freely given means no pressure, guilt, or manipulation. If you feel afraid to say no, it's not consent. You must decline without negative consequences.

- Reversible means you can change your mind at any time, even if you've agreed before. Partners must respect a withdrawn "yes" immediately.

- Informed means you have all the honest, relevant information. You can't truly consent to something if you don't know what you're consenting to.

- Enthusiastic means you actively want to participate, not just tolerate it. Consent is an enthusiastic "yes," not just the absence of "no."

- Specific means consent for one thing doesn't apply to everything else. Agreeing to your partner dating someone doesn't mean you've consented to them spending every weekend away. Each situation needs its own consent.

How do boundaries function in relation to consent?

Boundaries are the lines that protect your well-being. In polyamory, boundaries and consent are inseparable; your boundaries define what you are and are not consenting to.

Think of boundaries as the framework for consent in polyamory. They include personal limits (activities, emotional energy), relationship agreements (how connections function), sexual boundaries (safer sex, specific acts), emotional boundaries (intimacy levels), time boundaries (preventing neglect), and communication boundaries (what information is shared). Everyone must agree on these.

Boundaries aren't set in stone; they evolve. The key is to continuously communicate about them and respect them as they change. When someone violates a boundary, they violate consent. If you're dealing with Relationship Issues around boundaries, professional support can help everyone honor each other's limits.

How Can Power Dynamics and Coercion Affect Consent?

Power imbalances exist in most relationships, stemming from differences in income, experience, or social confidence. In polyamory, couples' privilege adds another layer, where an established couple holds more power than newer partners.

When unacknowledged, these imbalances can corrupt consent in polyamory. What looks like agreement might be compliance from someone who feels they have no choice. Real consent requires the freedom to choose, and when one person holds significant power over another, that freedom disappears.

What are the signs of coerced consent or consent under pressure?

Coerced consent is not consent at all; it's compliance. The pressure can be subtle or obvious, but it results in someone saying yes when they are afraid to say no.

Warning signs include:

- Fear of loss: Agreeing to open a relationship to prevent a breakup.

- Guilt-tripping: Using phrases like "I thought you loved me" to override boundaries.

- Threats of breakup: Direct or implied ultimatums.

- Withholding affection or applying constant pressure after hearing "no."

The #MeToo movement highlighted how power dynamics can create coercion without explicit threats. When someone has financial, professional, or emotional leverage, an agreement made out of fear of consequences is not genuine consent.

When does discomfort or jealousy cross the line into non-consent?

Jealousy and discomfort are normal emotions in polyamory and don't automatically mean consent was violated. Sometimes, discomfort is a signal to adjust a boundary or an opportunity for personal growth.

The line is crossed when someone's expressed feelings are ignored, dismissed, or used against them. If a partner dismisses struggles with "Well, you agreed to this, so deal with it," that's a problem. If someone grudgingly accepts a situation because they fear being called insecure or "not poly enough," their agreement isn't truly consensual. The difference is agency: are you choosing to work through difficult feelings because you want the relationship structure, or are you trapped? Polyamorous couples therapy can help clarify this.

What are the ethical implications of using consent as an excuse for abuse?

Some people weaponize the language of consent to justify harmful behavior, hiding behind statements like "You agreed to this" to rationalize abuse.

Consent is never a shield for mistreatment. Agreeing to polyamory doesn't waive your right to safety, respect, or dignity. Using consent as an excuse invalidates feelings and blames the victim, removing accountability from the person causing harm. The myth of blanket consent is dangerous; each interaction requires its own specific consent. As the community saying goes: "Polyamory does not equal consent."

What is the Role of Communication in Ensuring Consent in Polyamory?

If consent is the foundation of ethical polyamory, then communication is the mortar holding it together. Genuine consent in polyamory requires ongoing dialogue, not just one big conversation. It demands constant check-ins, active listening, and honest sharing.

Communication bridges the gap between your thoughts and your partners' knowledge, preventing the assumptions where consent breaks down. Open communication creates a safe environment for expressing feelings, setting boundaries, and saying no. Honesty and transparency are essential; hiding information undermines your partners' ability to give informed consent. Real Communication means sharing the full picture.

What are the responsibilities of individuals in a polyamorous relationship?

Maintaining ethical consent is a shared commitment. Key responsibilities include:

- Self-awareness: Understand your own needs, desires, and limits before you can communicate them.

- Clear articulation of needs: Your partners can't read your mind. State your needs, comforts, and discomforts directly and honestly.

- Respecting partners' boundaries: When someone tells you their limit, believe and honor it without trying to negotiate their feelings.

- Taking responsibility for your own emotions: Your feelings are valid, but they are yours to manage. Partners can offer support, but blaming them can lead to coercion.

- Proactive communication: Bring up issues, new interests, or the need to renegotiate boundaries before they become major problems.

- Safer sex agreements: This is non-negotiable. All partners must be informed of any changes in sexual risk so they can make their own informed health decisions.

How does communication ensure informed consent in polyamory?

Communication makes abstract consent concrete and actionable.

It involves disclosing new partners to provide essential information that affects everyone's emotional and physical well-being. Discussing changes in risk profiles is also critical; if safer sex practices change, everyone affected needs to know immediately so they can decide their own comfort with the risk. This is part of exploring exploring the various forms of love and ways to recognize them while prioritizing health.

Communication is also key for negotiating agreements about how your relationships will work, preventing misunderstandings and hurt. It creates a space for expressing desires and limits without judgment, which is fundamental. Finally, it means preventing assumptions by checking in regularly. The moment you start assuming, you stop listening, and consent can slip through the cracks.

What Happens When Consent is Unclear or Violated?

Even in thoughtful polyamorous relationships, things can go wrong. Situations where consent in polyamory becomes murky or gets crossed are painful and shake trust, but they also present an opportunity to repair, learn, and strengthen your commitment to doing better.

When consent breaks down, the path forward depends on understanding what happened and why. The goal is not to assign blame, but to figure out how to heal and prevent it from happening again.

What is the difference between a consent violation and a 'consent accident'?

A consent violation is an intentional disregard for a boundary or agreement. It's a deliberate choice to prioritize one's own desires over a partner's consent, such as breaking a safer sex rule without disclosure or lying about seeing someone.

A consent accident, on the other hand, stems from miscommunication or misunderstanding. Harm is unintentional, but a boundary is still crossed, perhaps because it wasn't clearly communicated or assumptions were made. The key difference is the lack of malicious intent.

Both situations cause real pain and require repair. Understanding the intent helps guide the next steps. You can read more about navigating these complex situations at Consent Violations in Consensual Non-Monogamy.

How can individuals steer situations where consent has been violated?

When consent is violated, rebuilding trust requires accountability and changed behavior. It's a difficult process, but possible if everyone is willing to do the work.

- Acknowledgment: The person who caused harm must recognize what happened without making excuses. The impact on the harmed person is the priority.

- Center the harmed person's feelings: Listen to their experience without defensiveness. Validating their pain shows you care more about their well-being than your ego.

- Take accountability: Own your actions and their impact. A sincere apology acknowledges the specific harm, unlike deflections like "I'm sorry you feel that way."

- Discuss prevention: Analyze what went wrong to prevent it from happening again. This may involve renegotiating boundaries or having more frequent check-ins.

- Change behavior: Apologies are meaningless without action. Rebuilding trust requires demonstrating, over time, that you respect boundaries and have learned from the mistake.

Sometimes, the hurt is too deep to steer alone. Seeking professional support from a poly-affirming therapist trained in poly therapy can be crucial for healing and guiding everyone toward healthier patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions about Consent in Polyamory

Does agreeing to be polyamorous mean I consent to everything?

No. Saying "yes" to a polyamorous relationship structure is not blanket consent. Think of it like agreeing to go to a restaurant; you've agreed to eat there, but not to order every item on the menu.

You are consenting to a framework where multiple connections are possible, not giving your partner permission to act unilaterally. Consent in polyamory is specific and ongoing. Each new partner, sexual activity, or change to safer sex agreements requires its own conversation and enthusiastic consent. Your right to say "no" to any specific situation always remains intact.

Can consent be withdrawn after it's been given?

Yes, absolutely. Consent is never permanent. You can withdraw it at any moment, for any reason. While an explanation isn't required, communication is usually helpful for everyone involved.

For example, you might agree to your partner dating someone new but realize it's affecting you in unexpected ways. You can withdraw that consent. When someone withdraws consent, the only ethical response is immediate respect. The activity must stop without argument or guilt-tripping.

Is it a consent violation if my partner does something I don't like, even if I agreed to it?

This is a nuanced but important distinction. If you gave informed, enthusiastic consent and then didn't enjoy the experience, it's not a consent violation. It's new information about your preferences and boundaries. For example, you might consent to a partner's overnight date but feel unexpectedly uncomfortable. Your discomfort is valid, but consent wasn't violated.

A consent violation occurs without your genuine, informed agreement. This includes when a partner ignores a "no," lies about their activities, or manipulates you into agreeing. The key is distinguishing between "I consented but didn't like it" and "I didn't actually consent." The first calls for communication and adjusting agreements; the second is a breach of trust that requires accountability and repair.

Conclusion

Consent in polyamory is a living, breathing practice, not a one-time checklist. It requires honesty, careful listening, and openness to change. When you commit to ethical non-monogamy, you're committing to a continuous conversation where everyone's voice and boundaries are honored.

Maintaining genuine consent isn't always easy. It's built on transparency, self-awareness, and a deep respect for each person's autonomy. We've explored how consent must be freely given, informed, enthusiastic, specific, and revocable. We've also looked at how power dynamics can undermine it, how communication makes it possible, and what to do when things go wrong. These are the daily practices that separate ethical polyamory from relationships built on pressure or fear.

When violations happen, the path forward is through accountability and empathy. Navigating these complex dynamics can be difficult, and professional help can make a significant difference.

If you're working to build healthier communication, process difficult emotions, or repair trust, you don't have to do it alone. Kinder Mind offers accessible therapy with professionals who understand the unique challenges of polyamorous relationships. They can help you develop the skills to create relationships where consent thrives. Whether you're new to ethical non-monogamy or experienced, a supportive therapist can help you steer the complexities with more confidence and care.

Get support navigating your relationships with couples therapy